Murtaza Dhamangamwala

It is well known that the built environment has an immense impact on our physical and psychological wellbeing; and architecture, the art of design and construction of the built environment, governs this influence. People, in turn, shape and fashion architecture based on the principles they hold dear, such as culture and technique. Modern architecture is often criticised for its globalised approach, a culture of mass consumption, devoid of contextual aesthetics [1]. After all, so is the modern man, ever consumed in the affairs of worldly matters, in chase of dreams which lure him away from the spiritual realm.

And so, just the way a spiritual break can nourish our souls, a well-designed and sensitive building can help calm our minds and rejuvenate our health. Burhanpur is one such example of an oasis of spiritual relief in a desert of ceaseless materialism. This is why the Mughals called this town Dar-ul-Suroor – the place of happiness; a name that Doat Mutlaqeen have also used. Burhanpur is a small historic town in central India, which was an important city during medieval times. However, for mumineen, the place has always been associated with their awliya, especially Syedi Abdulqadir Hakimuiddin QR. The serene white mausoleums amidst a vast marble courtyard in the mazar provide an ideal setting to reflect and contemplate on one’s actions.

The mausoleum of Syedi Abdulqadir Hakimuiddin QR was completed by the 41st Dai, Syedna Abduttayyib Zakiuddin RA, in ca. 1195 H/1781 CE. The structure was refurbished in 1405 H/1984-5 CE under the direction of Syedna Mohammed Burhanuddin RA. The external façade of the original structure was recreated in white marble during the renovation, whereas the interior was enlarged [5]. The design and aesthetic style is similar to other qubab mubaraka in Surat, Ujjain, Denmal, Galiyakot etc. which were originally built before the revival of Fatimi monuments from 1401 H/1980-1 CE onwards. The building is in the form of a cubic body, resting on a small plinth, surmounted by a bulbous dome. Each side of the building has a decorative portal which extrudes slightly outward. The square base ends in a projected parapet, which is supported by a series of 38 brackets (corbeling) on each side and one each corner. The square base is transformed into an octagonal tambour by squinches at the corners.

The ribbed dome rests on a cylindrical drum rising above the octagonal supports. The lustrous mausoleum is perfected by a golden filial placed atop the dome, adding emphasis to the entire body. While the dome is a huge structure in itself, its sheer size and magnitude can only be appreciated when juxtaposed with another element. Thus, the 12 minarets located on the corners of the cubic and octagonal body serve to provide a contrast, and help viewers appreciate the vastness of the sepulchre.

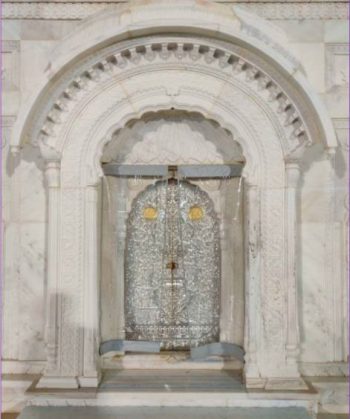

From a distance, one’s sight is drawn towards the dome of the qubba, achieved by the clever proportioning of the upper half of the mausoleum. However, as one walks closer, the intricate details and relief features on the walls become visible. The revelation is even more mesmerising when witnessed in the low sun. The white glare peels away to reveal the floral patterns covering the walls, the cusped archway above the doors, the recessed niches covered with vegetal patterns, flutings in the columns, the carved frieze above the parapet and the inverted lotus above the dome. By now, the Qubba has established a connection with the yearning soul, conveying tranquil emotions and beckoning inside. It is only now, when entering, does the eye spot the silver door–exquisite with floral designs.

The hallowed space within exudes grace and charm, and all those who enter are visually drawn towards the chatri covered qabr mubarak of Syedi Abdulqadir Hakimuiddin QR. It is only after the eyes have soaked in the noorani manzar and shed a tear or two in reverence, that they observe the intricate details of the marble work, niches in the walls, the Quranic inscriptions and the mudawwara at the centre of the dome with a chandelier. The hum of dua and ibadat, reverberating in the qubba, complement the enchanting visual journey.

The time when the qubba was built was marked by intense political strife in the history of the subcontinent. With the Mughal Empire in decline, there were regional rulers and colonial powers establishing their dominion. This also meant there were many varying archetypes and concepts for building construction. The use of chatris (trabeated domed canopy) over the doorways is an interesting feature in the qubba mubaraka. This design style conjures the image of western Indian regions, such as the Shekhawati region in Rajasthan which is renowned for its chatris, brackets and wall paintings [3]. However, chatris have been used in other places much before they made their way to India. They existed in varied forms in a number of places such as Cairo and Isfahan, and were used as cenotaphs and memorials [2]. These were possibly made of wood, however, once the feature was introduced in India, it was replicated and perfected in stone as this was a common material in use then. Few distinct designs of chatris evolved in India and can be seen in many palaces and forts. Despite the rich variance and variety of chatris all over the world, the chatri in the qubba mubaraka has possibly been inspired from its Indian counterparts, as it most closely resembles them.

The dome, similarly, resembles that of the Timurid design style which was refined in the Mughal era. A similar dome can be observed in the mausoleum of Khoja Ahmed Yasawi, built in Turkistan, towards the end of the 14th century, which is considered a UNESCO world heritage site. In the Dargha-e-Hakimi, the dome is smaller but is balanced by ornamentations and the use of bright white marble. The addition of minarets around it gives it a graceful appearance and poises the proportions- a concept applied in many Mughal buildings. A second marble canopy inside the qubba is also a popular feature which can be seen in, for instance, the Sa’dian tombs of Marrakesh [4].

The amalgamation of these diverse elements in a meaningful way thus represents the symbol of the qubba, and an identity of the larger socio-cultural context. A design motif by itself has no meaning, unless associated with something. There was a need to design an enclosure to protect the qabr mubarak as well as allow mumineen to pay respect to their awliya. The architecture was thus shaped by the socio-cultural context of the time, deriving inspiration from artefacts considered auspicious. The qubba mubaraka, in turn, makes a profound impact on the attitude and psyche of the people. While it is true that the aura of the space can be enhanced by the subtle interplay of form and texture, the fact remains that a space can only truly stimulate one’s spiritual senses if it holds a relic of historic significance. For instance, the holy graves of the Ahle Bait SA in Madina will be perpetually revered, regardless whether a zari honours their location or not. Architecture should only facilitate to enhance the experience and not merely provide a functional response [6].

References

1. Frampton, K. (2019). Towards a Critical Regionalism. Six Points for an Architecture of Resistance. Critical Regionalism

2. SHOKOOHY, MEHRDAD, and NATALIE H. SHOKOOHY. “The Chatrī in Indian Architecture: Persian Wooden Canopies Materialised in Stone.” Bulletin of the Asia Institute 15 (2001): 129–50. http://www.jstor.org/stable/24049042.

3. In Photos: One Architect Saving Rajasthan’s Hauntingly Beautiful Shekhawati Havelis, accessed 5 July 2022, https://www.thebetterindia.com/214086/rajasthan-heritage-shekawati-havelis-conservation-delhi-architect-photo-story-say143/

4. Blair, Sheila., Jonathan Bloom, and Richard Ettinghausen. The Art and Architecture of Islam, 1250-1800. New Haven, Conn.: Yale University Press, 1994. Print.

5. Taabir Dar-al-Suroor, Aljamea-tus-Saifiyah Publications 1414 H/ 1993 CE

6. Libeskind, Daniel. Daniel Libeskind : the Space of Encounter. London: Thames & Hudson, 2001. Print.

Disclaimer–Viewpoints in blog posts do not necessarily reflect those of RadiantArts.

About the Author

Murtaza Dhamangamwala is a doctoral researcher at the University of Nottingham, UK. He is an architect by degree and has received his training from IIT Roorkee, India and HSLU, Switzerland. He has worked in various organizations as an architect and a sustainability consultant, including the Govt. of India where he helped design an innovative transport model for public EVs. His research interests lie in the domain of sustainable architecture and urbanism, energy efficiency, parametric design and building performance simulation. His current research focuses on ventilation and transmission of airborne pathogens in built environments.

Leave a comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.